A Beginner's Guide to Deep Learning (Part 1)

What To Expect From This Post

I'm not a PhD graduate. I don't develop self-driving software for a living. I'm just a programmer. But I have taken a few machine-learning courses. And I've also written a self-teaching Super Smash Brothers Bot using Deep Learning. So I'm not an expert, and I'm approaching this topic from a practical persecptive, and not an academic one, but I think I have enough of an understanding to help complete beginners write their first Deep Learning program. If you find yourself intrigued by this post, I encourage you to do more in-depth research on your own!

What is Deep Learning

If you've stumbled upon the term, "Deep Learning", then congratulations! You're one step closer to disambiguating the difference between "Machine Learning" and "Deep Learning". The side-effect of technology permeating pop culture (i.e. self-driving cars, virtual assistants, etc) is that the term "Machine Learning" tends to be used as a catch-all term for "the computer is acting smart, and I can't explain why".

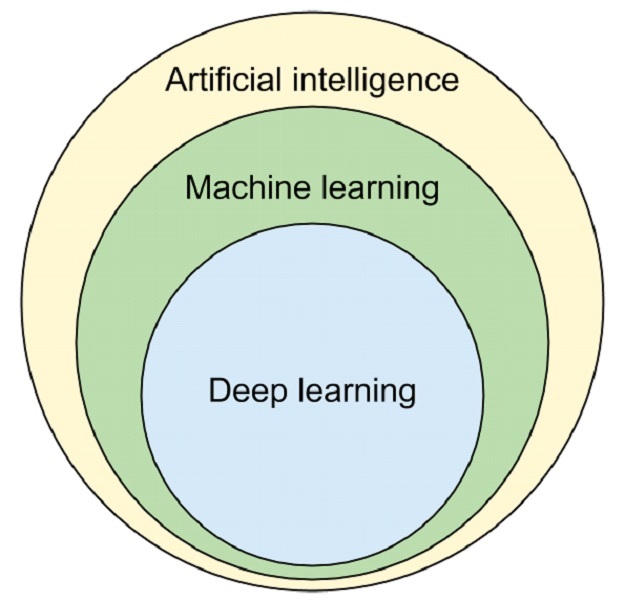

So, the very fact that you're trying to figure out, exactly, what Deep Learning is means that you've detected some kind of fundamental difference. And there certainly is. Or rather, Deep Learning can be thought of as a subset of Machine Learning concepts.

Deep Learning shares many similarities to traditional machine learning, has its own unique traits. Taken From Here

Deep Learning shares many similarities to traditional machine learning, has its own unique traits. Taken From Here

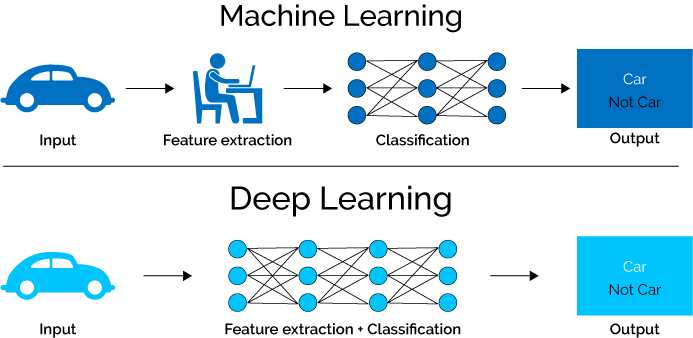

So What's Different About Deep Learning? These next paragraphs are a massive oversimplification, but to blithely summarize years worth of research, the biggest difference is that in traditional machine learning, you (meaning humans) would need to identify the important aspects, or "features" of an algorithm for the the machine to learn from by hand.

For example, if you were to design a system to learn how to recognize images of cats using traditional ML algorithms, you would need gather your cat-gineers in a room and decide what kinds of cat-ecteristics your system would need to learn and detect, such as

- Does it have whiskers?

- Does it have ears?

- Does it have a tail?

- Is it a dog instead of a cat?

For this simple cat-based task, constructing such a list would be pretty time-consuming, but for non-trivial tasks like automated self-driving vehicle tasks, it would be impossible. But let's say we wanted to do it anyway for this cat-detecting task. The final list would stil be prone to error: how would we be able to distinguish cats from tigers? Dogs from Cats? Yellow Cats from Lions? The list goes on. For humans, this task of "feature engineering" is a very difficult one.

Deep Learning seeks to address this pain-point by being able to "auto-magically" determine which features of the image were important for recognizing cats. It can even derive features that we, as humans, may not even think of that are useful in it's cat-detecting task.

How can it do this? It can perform something called "Feature Exaction" through the use of some clever algorithms and an important data structure called a "Neural Network", which is explained in the next section. The end result is that, instead of humans having to decide how to pick apart the pixels of an image to determine if it's a cat, the raw image can be fed into the algorithm.

Deep Learning handles the time-consuming and error-prone task of feature extraction for us. Taken From Here

Deep Learning handles the time-consuming and error-prone task of feature extraction for us. Taken From Here

Neural Networks As the Building Block for Deep Learning

Despite the recent hype surrounding them, Neural Networks are not newly-invented data structures. But they've become powerful tools for solving problems only until recently because their usefulness hinges upon two things:

- Having lots and lots of data

- Being able to compute lots of mathematical operations in parallel

I'd argue that perfect storm of cheap storage, readily-available parallel-compute units (i.e. GPUs), and scalable computing like AWS and Azure made the early 2010's the perfect time for Neural Networks to make a comeback.

What are Neural Networks

Simply put, Neural Networks are data structures made up of three components:

- Nodes

- Edges

- Layers

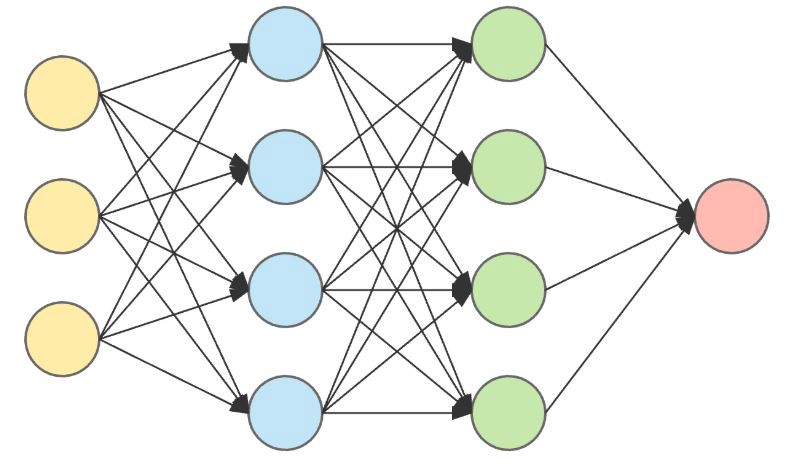

The images below shows a small example Neural Network, showcasing these three components in action:

A Simple Neural Network with and Input Layer, Two Hidden layers and an Output layer (from left to right). Taken from Here

A Simple Neural Network with and Input Layer, Two Hidden layers and an Output layer (from left to right). Taken from Here

The input layer consists of the three yellow nodes on the left, and they all have edges pointing to each one of the nodes in the next layer, and so on and so forth, until they all reach the final output layer on the right.

To understand how the model works, you need to understand a little bit of the math behind it (I'll keep it light and brief, so I'm simplifying things a little, here): starting at the input layer (which could represent anything, like RGB pixel values of a cat, audio data, etc. it just needs to be able to be represented numerically), this is what happens:

- An input node receives a value

- It sends it's value to all other nodes in the next layer

- Before the value reaches a particular nodes in the next layer, the value is multiplied by that specific node-to-node edge-weight (this is important)

- The receiving node sums all of the values it's received, and passes the value onto all of the nodes in the next layer (a simplification but enough for now)

- Do this for all nodes, for all layers, until we reach the output.

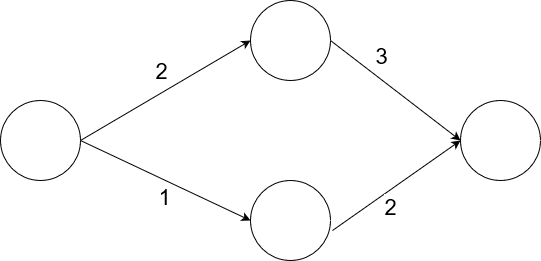

A very simple network. See below on how to compute the output

A very simple network. See below on how to compute the output

Take the network above as an example. Let's say we have "3" as an input. To compute the output, here's what would happen:

- The top node would receive

3 * 2 = 6 - The bottom node would receive

1 * 3 = 3 - The output node would receive

(3 * 2) + (6 * 3) = 24

We used whole number for our example, but for many problems, fractions and percents are used to express probabilities (i.e. an output might be expressed as a number between 0 and 1 to determine the system's confidence that an image is a cat).

This might seem completely ridiculous: how will a trivial model like that be able to solve complex problems? Well, the answer lies within the node-to-node edge weights. Each edge has its own, specially-tailored value that is meant to modify the outgoing signal to the next node, which is meant to modify that node's output, and so on. Therefore, each edge weight has a subtle, but important, impact on the final output of the model.

Crucially, with the right edge-weights, specifically tuned for a given problem, the model will be able to produce the desired outputs when given certain inputs. And by using many more nodes and layers, and taking advantage of the cross-referencing nature of the model the system can correlate and leverage the many-to-many associations between inputs, nodes, and layers, and make inferences about the data on its own. This is why Deep Learning models using Neural networks don't necessarily need feature engineering like traditional ML methods.

Training A Neural Network via Backpropagation

But the caveat to the hyperbolic statement above is that you need the correct edge-weights. You can't simply construct a Neural Network with nodes, edges, and layers, and just guess yourself some edge weights and call it a day. These weights are not something that can simply be guessed through brute force; rather, they the component in the model that must get "trained". And they can only get trained by having lots of data (along with the answers to that data, i.e. a "labeled" data set) with which to train your model.

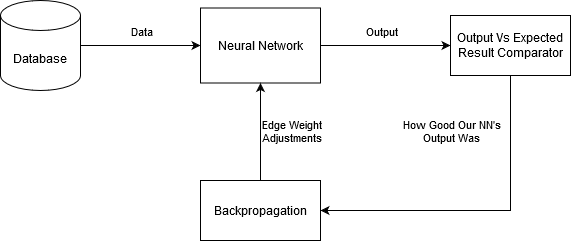

Training a Neural Network Goes something like this, again simplified for brevity:

- Get your raw data from somewhere (again, could be image data, medical data, etc).

- Initialize your edge weights to something random

- Transpose the data into the dimensions that fit your Neural Network Input Layer

- Feed it into the network and get the output

- Compare the output to what the answer SHOULD be

- Use "Backpropagation" and a "Gradient Descent" algorithm to adjust the edge weights so that, the next time you see the same inputs, the output will be nudged a little closer to the right answer.

A simplified Neural Network Training Diagram

A simplified Neural Network Training Diagram

I'm handwaving backpropagation and gradient descent for now, since it involves a lot of advanced math which I don't think is super relevant for beginners looking to simply get their feet wet in this field. So simply know that it's a powerful mathematical technique to efficiently adjust the edge-weights of your Neural Network to get closer to the right answer. Think of it has a sophisticated, advanced version of guess-and-check.

In short, a lot work has been put into backpropagation and gradient descent so that, when your network produces a result that's wrong, your network's edge weights get updated so that they'll be less wrong upon seeing the same inputs again. It's important to note that we don't want to drastically alter the edge weights' values: we don't want one single example to have a huge effect on the training (what if that single example is an outlier, like a weird looking cat?), but at the same time, we don't want the change to be so little as to not have any effect at all.

After going the 6-step process above many, many times, your network will eventually start to converge on a set of "good-enough" edge weights that will work great for your training data set, and if done correctly, should work for data that it hasn't even seen before (which is the whole point of machine learning!).

Deciding How Many Nodes, Edges, and Layers to Use in a Network

The final question you may be wondering is: how do you determine the number of nodes or layers in a network? Unfortunately, there aren't many hard-and-fast rules, but rather, some accepted guidelines:

- The more nodes, the more that your model can learn, but it will take longer for your model to learn and execute (and it's possible that your model may learn nothing at all if there's too many nodes)

- For all but the most complex problems, 2 hidden layers may be enough.

- Look for prior work similar to yours, and use similar network structures as a starting point

- Simply experiment with different network parameters for your particular problem.

I found the last bullet point the most useful, as I saw absolutely terrible performance for my project using 2 hidden layers with 256 nodes since, I dunno, that seemed reasonable. Performance was so bad that I was convinced that I had an implementation bug somewhere, and literally spent months re-writing everything. It wasn't until, on a whim, I increased my network to 4 hidden layers with 1000 nodes that I saw performance skyrocket. This could have been due to an inefficiency somewhere, but nevertheless, I still kick myself for not simply experimenting with network structure earlier on.

Summary

Hopefully, this has given you enough of an understanding for my next post, which will dive into using Keras, a library with powerful Deep Learning tools!

Comment Policy: no flamewars or trolling. Just have fun and be nice!